Deep Dive: Aston Martin Lagonda

Continuing my valuations of car companies, this time it's Aston Martin's turn

Aston Martin is a highly regarded prestigious British sports car manufacturer, but one with a chequered financial past. Having had a difficult time of late, and now hovering close to 52-week lows (arguably close to all-time lows), is there an opportunity here, or has the market priced AML effectively?

History

The company now known as Aston Martin Lagonda was founded in 1913 by Lionel Martin and Robert Bamford1. Previously, the pair had sold and serviced cars under the name Bamford & Martin, but, being disappointed with the quality of the cars they were working with, they decided to make their own2. Almost immediately after setting up shop, World War 1 interrupts their plans. After the war, based out of premises in Abingdon Road, Kensington, London, they produce two racing cars - the TT1 in 1922, nicknamed ‘Green Pea’, and the TT2, funded by racing enthusiast Count Luis Zborowski, who invested £10,000 (which I calculate to be equivalent to around $836,000 today3) to develop a new 4-cylinder, 16-valve, twin overhead camshaft racing engine. For those of you familiar with your engines, this is an architecture which is not out-of-place today! Although originally intended for the Isle of Man TT, delays meant the TT1 and the TT2 debuted at the French Grand Prix in 1922 instead. In the 1920s, Bamford & Martin start taking their cars to Brooklands circuit in Surrey, a circuit also linked to Bentley, who were founded at a similar time (1919). Bamford & Martin’s cars start setting speed and endurance records at this track. In 1923, Bamford & Martin create the first chassis they will sell to the public, the ‘Razor Blade’, of which they make around 55 examples.

In 1924, the company now known as Aston Martin went bankrupt for the first time. They are bought out of bankruptcy by Lady Charnwood, whose son, John Benson, joins the board. In 1925, Lionel Martin is forced to sell the company to a group of investors, including Lady Charnwood, who rename the company Aston Martin (and so a legend is born).

Under the technical direction of Bert Bertelli, brought into the company through his relationship with William Renwick (who was part of the consortium of investors who bought Aston Martin with Lady Charnwood), Aston Martin produced a series of cars which developed a successful track record in national and international motor racing, including at the Le Mans endurance race.

In 1932, Aston Martin again ran into financial trouble, being rescued by Lance Brune, before ending up in the ownership of Arthur Sutherland. In 1936, Aston Martin decided to focus on road cars, before production was interrupted by World War 2. After the war (actually in 1947), David Brown (soon to be famous as the source of the ‘DB’ series of Aston Martin products) assumes ownership of Aston Martin and also of a company called Lagonda, to access its Bentley-derived engine. Consolidating operations in Newport Pagnell, Aston Martin created a series of successful grand touring cars under the DB banner, notably the DB4, DB5 and DBS. It is the DB5 with its 4-litre engine that starts the association with the James Bond franchise, featuring in Goldfinger and Thunderball. Under David Brown’s stewardship, Aston Martin wins the Le Mans 24hr race in 1959 with the DBR1, piloted by the famous Carroll Shelby (you may have heard of the Shelby Cobra? Or the 1966 victory of Ford over Ferrari at Le Mans with the Shelby American GT40? Same person) and the Formula 1 driver, Roy Salvadori.

In the 1970s, again in financial distress, David Brown sells Aston Martin to a consortium of investment banks led by William Willson, and then to another consortium of American, Canadian and British businessmen. In 1975, the company re-opened its factory as Aston Martin Lagonda Limited. In 1977, Aston Martin Lagonda (AML) produce the first V8 Vantage. In the 1980s, AML again changes ownership, several times, until Ford takes a substantial 75% stake in 1987, before taking full control in 1991.

The 1990s and early 2000s mark the decade with the cars that made the biggest impact on me, personally, with the DB7, DB9 and, of course, the V12 Vanquish.

In 1999, Ford establishes its Premier Automotive Group, a division of the company to hold its most prestigious marques, including Aston Martin Lagonda, Volvo, Lincoln, Mercury, Jaguar and Land Rover. In 2003, Aston Martin move their headquarters (but not all manufacturing operations) from Newport Pagnell to Gaydon in Warwickshire, next door to stablemate Land Rover. In 2007, Ford sells 92% of Aston Martin to a consortium headed up by Dave Richards, the chairman of motorsports operation Prodrive, best known for its world rally exploits, based out of Banbury in the UK. In the same year, Aston Martin transfer the last of their production manufacturing operations from Newport Pagnell to Gaydon.

In the 2010s, AML launch a succession of cars familiar to most enthusiasts, with a new version of the Vanquish (and special editions like the GT12), the Vulcan, the GT8 Vantage and the DB11. 2013 sees a tie-up with Mercedes Benz (at the time, trading as Daimler Group), with AML getting access to Mercedes-Benz’ AMG engines and with Daimler taking a stake in AML of up to 5%4. By 2020, Daimler’s stake in AML had increased to 20%. At the end of the decade (2019), AML opens a new facility in St Athan in Wales to produce their new Sports Utility Vehicle (SUV), the DBX.

The 2010s also saw some significant changes in ownership and leadership. The decade started under the leadership of Dr Ulrich Bez, formerly of Porsche and BMW and a keen racing driver, who was brought in during the Ford era. Bez was succeeded by former Nissan executive, Andy Palmer, who led the company from 2014. In 2018, under Palmer’s watch, AML underwent its Initial Public Offering. The IPO valued AML at a little over £4bn, whereas AML had hoped for a valuation nearer £5bn.

And to bring us up to date, the 2020s start with Lawrence Stroll leading a consortium to take a 16.7% stake for £182M, valuing AML at just over £1bn5. At the same time, AML commits to a rights issue to raise £318M and commits to rename the former Force India F1 team, then owned by Lawrence Stroll and known as Racing Point, as Aston Martin F1 from the 2021 season. Stroll would later increase his holding to 25%. Also in 2020, Andy Palmer is succeeded by Tobias Moers from Mercedes Benz AMG. However, the year ends on a sour note, with a controversial report by Clarendon Communications6, a company set up earlier in the year under the name of the wife of Aston Martin’s director of government affairs, claiming to use data from Polestar and Volkswagen to imply that petrol cars have lower CO2 emissions than electric cars for the first 78,000 km of use. The report is rebuffed for not considering all sources of emissions and the Chartered Institute of Public Relations condemns obfuscation of sponsors as a breach of their code of conduct7

2021 brings the mid-engined hybrid vehicle, the Valhalla, and the halo product, the Aston Martin Valkyrie. The Valkyrie had a bespoke 1000 bhp, 6.5-litre V12 developed specifically for the vehicle by racing specialists Cosworth in the UK, capable of revving up to 11,100 rpm. The Valkyrie also included a hybrid system developed by Rimac and Integral Powertrain. The hybrid system is used for a boost / launch function, rather than increasing the maximum powertrain torque or power, both of which are achieved by the engine on its own8.

In 2022, AML undertakes another rights issue, this time a 4-for-1 issue at 103p per share to raise over £575M, with Lawrence Stroll’s Yew Tree consortium, the Saudi Arabian Public Investment Fund and Mercedes Benz’ collective stakes accounting for 44.7% of the issue9. The rights issue declares the funds will be used to increase liquidity, pay down debt and enable Aston Martin to generate positive free cash flow from 2024. Based on the closing price of the prior day, the rights issue should have provided shareholders with a share price of 178p ex-rights, suggesting a market capitalisation of around £1.2 bn. Tobias Moers is succeeded as CEO by ex-Ferrari CEO Amedeo Felisa.

In 2023, Geely took their stake up to 17%. AML signed a 10-year technology agreement with Lucid Motors (actually, with a Lucid subsidiary, Atieva) for its electric powertrain systems, in exchange for a 3.7% stake in AML and cash of $132M10.

Which brings us to 2024, and the appointment of ex-Jaguar Land Rover and ex-Bentley executive, Adrian Hallmark, as CEO on 1 September. On 30 September, AML issued a profit warning, stating they no longer believed they would get to positive free cash flow in 2024, but saying their 2025 targets (£2 bn revenue and £500M of adjusted EBITDA) remained intact. On 27 November, AML announced the placement of 111M new shares at £1 per share, and £100M of new debt. Currently, the Aston Martin market capitalisation is very approximately £1 bn.

Show Me The Money

Segments and Revenue

AML segment their sales by geographical area, but they also provide good insight into their sources of revenue between vehicle sales, parts, servicing and branding activities, and split out their vehicle sales by type. So how have they been doing?

From 2018 to June 2024, on a trailing twelve month basis, revenue has grown by 42%, whereas vehicle sales have actually dropped by 12% in the same time. This works out as a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of around 6.6% for revenue, with around a -2.3% CAGR in vehicle sales. Over 90% of AML’s revenue comes from vehicle sales, so it is not a surprise to learn that AML’s sales revenues have achieved a CAGR of 6.8% since 2018, slightly more than the overall revenue CAGR. Parts sales have increased at a CAGR of 5.6%, while servicing revenue has dropped by over 3.5%. Revenue from brands and motorsport has been fairly flat, with a CAGR of 0.9%. Over the last twelve months, total revenue is up around 2.7%, so current growth is lower than has been seen, in aggregate, since 2018.

Looking at where vehicle sales are coming from, Figure 2 shows that in the late 2010s, AML was fairly evenly split across its 4 regions, but in more recent years, sales have been tending away from the UK and towards the Americas and mainland Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA). 2020 obviously saw a severe decline in sales, with a significant bounce back in 2021, however, over the last twelve months, the number of units sold has dropped over 15%, with the largest decline in the Americas (-31%) and Asia-Pacific (-22%). EMEA is the only region currently showing growth, with sales increasing 6% in the last year. Figure 3 shows that the majority of the drop in sales over the last year has come from a drop in SUV sales, which have declined 48%, while Sports and GT cars have only declined 7%. However, the Sport/GT segment has declined substantially since 2019. Even though the segment dropped 68% from 2019 to 2020 and then increased 70% from 2020 to 2021, the Sport/GT segment has shown an annualised decline of 26% between 2019 and 2021, and an annualised decline of 12% from 2019 to the 2024 first half-year results.

Despite the drop in sales, the average selling price has been increasing recently, particularly for AML’s “Special” products, like the Valkyrie hypercar, and limited-edition models like the DBR22, Zagato products, or the James Bond DB5 continuation models from a few years ago. AML’s core products had an average selling price of £180k - £190k in 2023, whereas the average selling price across all models was over £230k at the same time, and is now over £250k.

To recap, AML has seen strong revenue growth since the lows of 2020, but this growth has slowed recently, with less than 3% total revenue growth over the last twelve months. Revenue, which is dominated by income from vehicle sales, has been supported by strong growth in the average selling price, particularly from Specials. However, this is in the context of reducing vehicle sales, most significantly over the last twelve months, and most significantly in the Americas and Asia Pacific regions.

Operating Profitability

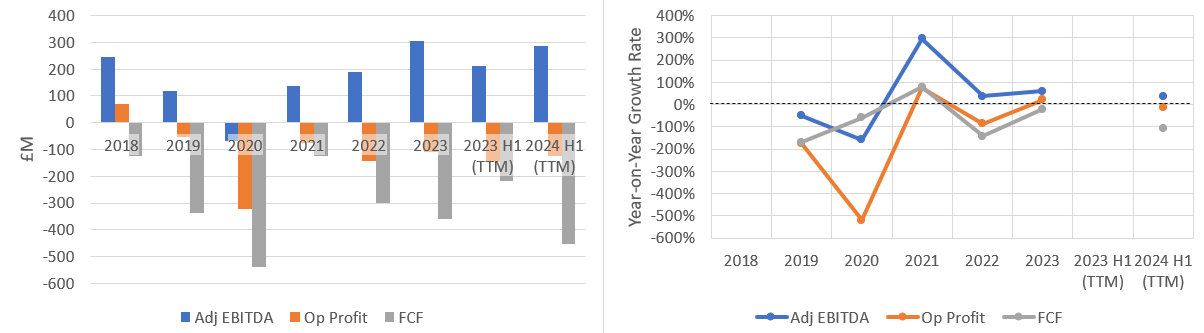

Income has been highly volatile for AML since 2018, with adjusted Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortisation (Adj EBITDA), Operating Profit and Free Cash Flow (FCF) often varying year to year by hundreds of percent. Although adjusted EBITDA has typically been positive, operating profit and free cash flow have been negative since 2019. In particular, negative free cash flow has doubled over the last twelve months, even though AML’s operating loss has been relatively stable.

Digging into the operating performance first, AML initially appears to have very healthy margins, generally achieving gross margins of 30% - 40%. Closer inspection reveals that a significant offset to the gross margin is caused by AML’s depreciation and, particularly, amortisation (D&A) expenses. In the absence of these costs, AML would be able to achieve gross margins in excess of 60%. In general, AML’s gross margin, excluding D&A expenses, has been improving, indicating that AML is able to grow its revenue faster than increases in the cost of its materials.

However, the amortisation costs are very real. International Accounting Standards, like IFRS or IAS, consider that money spent on development of new products should result in future financial benefit to the company, and therefore those development expenses are actually creating intangible assets (in this case, know-how for making specific cars). Consequently, the vast majority of research and development (R&D) expenses are capitalised, meaning they do not show up directly on the income statement, but instead the cost is expensed over a number of years, through amortisation of those intangible assets over the life of the product. In AML’s case, typically 90% to 95% of gross R&D expenditure is capitalised. With gross R&D expenditure equivalent to around 40% (or more) of the Selling, General and Administrative (SG&A) costs ultimately expensed to the income statement, this is a significant cost for Aston Martin that ultimately shows up as higher costs of revenues and lower gross margins.

Unfortunately for Aston Martin, the cost of developing vehicles is generally not scalable - it costs roughly the same amount to test and develop and homologate a car (verifying compliance with regulations like crash safety, emissions performance, plus market regulations for items like lighting, steering, braking, etc.) whether you sell one unit or one million units (although, actually, there are derogations to permit manufacturers of small numbers of vehicles to work to less stringent targets in some cases).

In AML’s case, the SG&A expenses are equivalent to around 40% of revenues and have been increasing at a CAGR of over 6% since 2018. Therefore, with gross margins (after D&A expenses) of 30% - 40% of revenue, but SG&A expenses of 40% of revenue, operating profit is under severe pressure and AML has been generating a loss through its operations since 2019. For the year to end June 2024, this loss was 8% of revenue, meaning it cost AML 108% of its income to continue its core business. Although the Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) margin for the year ending 30 June 2024 was better than a year ago, when the operating loss was nearly 10%, in my opinion, it’s too early to tell if this is the start of AML turning the tide. Typically, the first half-year shows worse operating margins than the second half-year, so perhaps the full year results for 2024 will build more confidence.

While discussing SG&A expenses, I’m going to call attention to AML’s employee expenses. Despite some volatility around COVID, AML had grown their employee count at a CAGR of 3.9% between 2018 and 2023. In that same time, AML’s staff costs only increased at a CAGR of 1.6%, meaning AML have in effect reduced per capita staff costs at a rate of around 2.3% per annum. However, this reduction was primarily achieved via a 35% reduction in per capita staff costs between 2018 and 2019. Since then, per capita costs have increased at around 8% per annum on average.

AML is also pushing hard to increase its female representation, which has remained stubbornly in the range of 14% - 16% in recent years. AML helpfully provide a breakdown in female representation by region, but it is fundamentally a British company, meaning its overall gender gap is very close to its UK gender gap. To scale this, of the roughly 2,700 global employees, around 95% are in the UK. For example, in 2023, there were 48 employees in the APAC region, 71 in the EMEA region, 41 in the Americas, and over 2,600 in the UK. Therefore the low representation of women in the workforce reflects the low representation of women in the UK engineering and technology workforce11

Financing Expenses

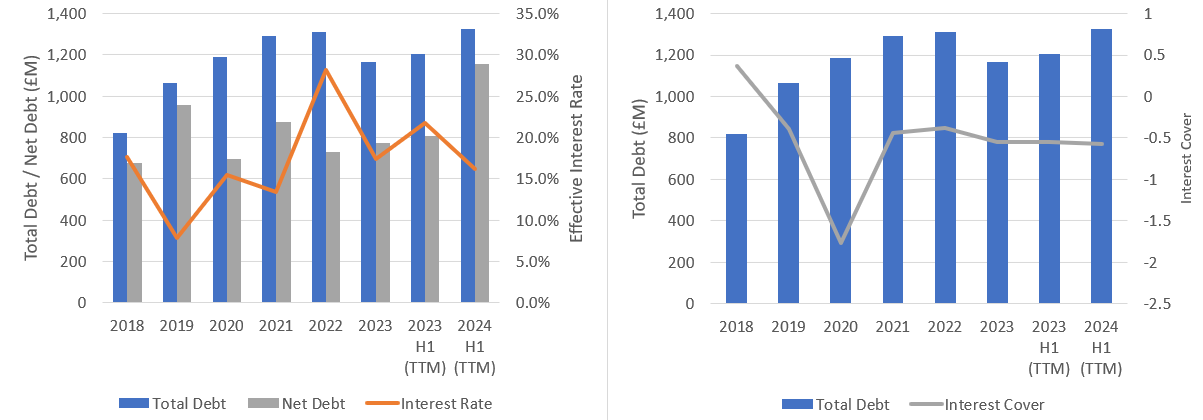

AML had been doing a reasonable of bringing their debt down in 2023. but it has increased again in the first half year in 2024. And, whereas net debt was markedly lower than total debt in 2022 and 2023 (i.e. the total debt had been used to release substantial amounts of cash), by June 2024, it had climbed back to 87% of total debt (i.e. cash reserves had reduced from a high of £583M in 2022 to less than £173M) by June 2024. The effective interest rate AML was paying on its debt has varied over the years, but has generally increased from around 8% in 2019, to over 16% in the twelve months to June 2024. In terms of affordability, interest cover has been running at around -0.5 to -0.6 since 2021, meaning AML’s interest expense is around 50% to 60% of AML’s operating loss but, being a loss, AML cannot afford any debt - the debt compounds its losses by 50% to 60% (Figure 7).

Being generally loss-making, AML is typically given tax credits, as opposed to having to pay a tax bill. Although AML did have a tax expense on its profit & loss accounts in 2022, at around a 23% rate, on average AML has been provided with tax credits of around £8M per year between 2018 and June 2024.

Earnings Per Share

AML has seen significant changes in the number of shares outstanding with their various rights issues in recent past, which obviously influences the earnings per share - the number of shares outstanding has increased at a CAGR of 28% since 2018. This is pretty heavy dilution for investors.

AML also has, on occasion, some substantial ‘adjustments’, leading to a considerable difference between their adjusted earnings per share and their statutory earnings per share. With the significant increase in shares outstanding, meaning the loss per share is heavily diluted, I believe the actual financial performance is not laid bare. The statutory loss has increased from around £60M in 2018 to a little under a £300M loss in the twelve months until June 2024. This reflects an increase in losses of around 33% each year between 2018 and the twelve months until June 2024. Although losses seemed to be improving through to the end of 2023, the first half of 2024 showed a degradation from AML’s 2023 position, and Adrian Hallmark’s trading update indicated the 2024 full year results will be degraded from its 2023 position.12

Cash Runway

Looking back at Figure 4, it can be seen that AML is consuming free cash flow at a rate of £200M to £400M a year currently. As of 30 June 2024, AML had cash and equivalents of £173M, meaning at the current rate of free cash flow, AML would possibly not even have one year of cash runway (closer to 5 months’), meaning AML either needs to access new capital (either through debt or equity), make more money from its operations, or spend less on capital investments for the future. However, the auditors concluded in 2023 that the use of a ‘going concern’ basis was appropriate, meaning they saw the means for AML to continue in business for at least 12 months from the date of that report. It is arguable whether or not the auditors perceived AML’s ability to continue beyond the end of 2024 without fresh capital - this year’s audit will prove very interesting to me.

With their 2024 half-year results, AML reiterated their 2027/28 targets of:

£2.5bn revenue at mid-40% gross margin, with

£800M adjusted EBITDA at ~30% margin

positive free cash flow

a total of £2bn of investment between 2023 and 2027, or roughly £500M per year

That level of revenue growth implies a CAGR of around 12%, or around £200M per year, but the EBITDA growth margin required is high - I estimate it requires a CAGR of around 35% (not allowing for the magnitude of adjustments, which may reduce this somewhat). Turning Free Cash Flow from -£400M to a positive value implies saving £100M per year. For a revenue increase of over £200M per year at a gross margin of mid-40%, Cost Of Goods Sold (COGS) can only afford to increase by around 10% per year, meaning COGS must fall as a percentage of revenue.

To get from £2.5bn in revenue at ~ 45% margin, to £800M EBITDA, with around £500M per year of capital expenditure, implies something around a 2% CAGR increase in operating expenses (excluding COGS) , which really isn’t much. Capital assets are depreciated over a period of up to 30 years, depending on the asset, so this is the number that I will assume for my valuation below (i.e. the increase in D&A expenses from year to year will be one-thirtieth of that year’s £500M capital investment).

As of 30 June 2024, AML had shareholder equity of around £761M, providing a book value of around £0.93 per share. This means a nominal debt/equity ratio for AML is something like 175%. However, due to the very high capitalised development costs, AML’s tangible book value (nominal book value, less intangible assets and less tax assets) is below zero.

Valuation

Because AML is currently loss-making, my usual valuation methods won’t work. But let’s assume AML’s management are correct. Let’s assume AML’s cost of equity is essentially their cost of debt, as they have no tangible equity to speak of, meaning I believe a reasonable discount factor is something like the 16% cost of debt currently being experienced.

Using the above assumptions for revenue, COGS, assuming no increase in debt (but also no decrease in debt), with a 16% discount factor, I estimate that AML is likely to continue to lose money until around 2026. In present value terms, by 2027, I would anticipate the accumulated value of AML to be around £350M lower than it is today. I would also estimate that AML will need access to another £1.5bn of liquidity to fund its capital investment, if its capital expenditure (CapEx) profile is spread evenly across the period from 2024 through 2027. AML’s half-year 2024 report indicates they have around £247M of liquidity and that car sales would need to drop around 30% to consume all of that liquidity, without adjusting capital spending. Therefore, I expect that the capital spending profile may not be as even as I have assumed, to smooth the cash consumption. In their Q3 earnings call, Doug Lafferty (AML’s Chief Financial Officer) suggested their liquidity would remain about £300M at the end of 2024, and that capital investment may be similar to 2023, i.e. more of the £2bn of capital investment declared in the half-year report might be back-loaded towards 2027. Lafferty also stated that AML is targeting being free-cash-flow positive in 2025, which I think would require a different revenue/EBITDA/CapEx profile than I have assumed here.

However, if these numbers are considered reasonable in aggregate, net income of around £125M in present value terms by 2027 would produce earnings per share in 2027 of around £0.15 in present value terms (if no further changes in share count). At a forward Price-to-Earnings (P/E) multiple of ~ 5, in line with other automotive OEMs, you could justify a current share price of around 76p. To justify the current price of around £1.05 would require a P/E of around 7 (based on 2027 earnings) - this is perhaps acceptable? Maybe a little pricey, but not ridiculous.

Conclusions

Aston Martin is a historic, storied brand. It has been through a number of difficulties, and changed hands several times in its history. It has recently been going through another set of difficult times, and has typically diluted investors to raise funds when it gets into trouble.

It has dropped heavily over the course of this year, but at its current valuations, it is within the realms of sensible values IF you believe that management can achieve very aggressive targets, looking to grow revenue by around 12% per annum and EBITDA by around 35% per annum from now until 2027. This is likely to require keeping COGS increases below the rate of revenue growth, increasing gross margin, and keeping increases in operating expenses to around 2% per annum, i.e. around, or a bit below, the likely rate of inflation.

This is not a stock for me at the current valuation - there is no margin of safety, given those aggressive targets, and I expect AML to need to access new capital before 2027 to achieve their targets. However, I will be very happy for someone to tell me I wasted an opportunity in a few years if Adrian Hallmark and his team can turn this ship around.

Do you think AML is fairly valued currently? Do you think it is a good investment at current prices?

Analyses and views presented represent my personal opinion and are intended for information purposes only. They should not, in any way, be considered to constitute financial advice or a recommendation to buy or sell any stock.

Aston Martin Lagonda website (astonmartin.com)

Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aston_Martin)

Currency conversions (https://canvasresources-prod.le.unimelb.edu.au/projects/CURRENCY_CALC/, https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1922)

https://www.manufacturingmanagement.co.uk/content/news/aston-martin-to-team-up-with-mercedes-on-engine-manufacture/

https://www.autocar.co.uk/car-news/industry/billionaire-stroll-takes-major-stake-aston-martin

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ahI9IxlZh1aD0_9cAOTR4VZFmhYWANj7/view

https://newsroom.cipr.co.uk/cipr-condemns-wholly-unethical-practices-involving-clarendon-communications/

https://media.astonmartin.com/aston-martin-valkyrie-the-ultimate-hybrid-powertrain-for-the-ultimate-hypercar/

https://www.astonmartin.com/-/media/corporate/documents/capital-raise-july-2022/rights-issue-announcement.pdf

https://www.astonmartin.com/-/media/corporate/documents/share-holders/lucid-shareholder-circular-29-aug-2023-final.pdf

https://www.engineeringuk.com/latest-news/press-releases/spike-in-women-aged-35-to-44-leaving-engineering/

https://otp.tools.investis.com/Utilities/PDFDownload.aspx?Newsid=1869755