Deep Dive: Bayerische Motoren Werke (BMW)

Continuing my analyses of automotive OEMs, today I am looking at BMW. Down 23% from a year ago, does it now represent good value?

As an engine development engineer in the automotive industry, BMW were often seen as the benchmark for marrying engine performance with good fuel economy. Growing up, the M3 and M5 were accessible cars for the enthusiast. But is that expertise still relevant as the market shifts towards hybrids and electric vehicles? Having a real soft spot for Munich as a city, I have always had an interest in BMW. Their headquarters (and BMW Welt) are definitely impressive buildings just across the road from the Olympic village (Olympiapark). I also have a keen interest in BMW because, like Daimler-Benz, they have also historically had a strong presence in aero engines, and they were a significant contributor to the German war effort. Regardless of your view on the German war effort (or any war effort), there is no denying that BMW have made some excellent engines over a long and distinguished history.

A (not very) Brief History of BMW

BMW started life as an aircraft producer, Otto Flugmaschinenfabrik, founded by Gustav Otto in 1910. Their first engine, the BMW IIIa, powered the World War 1 fighter, the Fokker D.VII(F), an aircraft which saw service with many forces (including Allied forces) after the War1. Otto Flugmaschinenfabrik became Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (Bavarian Aircraft Works) in 1916, and then Bayerische Motoren Werke (BMW) in 1922, when Franz Josef Popp transferred the name and assets from another company of which he was Managing Director, formerly Rapp Motorenwerke2.

BMW expanded into motorcycle engines following WW1. Max Friz3, Chief Engineer for the BMW IIIa, also designed BMW’s first motorcycle engine, the R-32, with its first motorcycle reaching production in 1923. By 1928, BMW had expanded into automotive production through the acquisition of Dixi, who produced Austin Sevens under licence, selling the first BMW car as the 3/15.

During World War 2, BMW focused on aero engine manufacture, with some very capable engines, like the BMW 800 and 801, which produced the first electro-mechanical computer-controlled unit to unload the cognitive effort from the pilot, particularly important with technologies like turbochargers as used on the BMW 801, which are extremely easy to overspeed at altitude4. BMW also used nitrous oxide injection and direct injection technologies during the war, technologies which only became commonplace in automotive engines (if you consider ‘nitrous’ to be commonplace, outside of street racing!) in the 1990s and 2000s.

(As an aside, for anyone with a serious interest in World War 2 technologies, I highly recommend getting your geek on and reading Calum Douglas’ book, The Secret Horsepower Race - he does a fantastic job of walking the reader through the war, year by year, and explaining what development work each country was undertaking at the time. It is very heavy on technical detail, which, as an engineer working in a related field, I think is fantastic.)

BMW restarted motorcycle production in 1948 and car production in 1952. They started expanding their range of performance-oriented saloons in the 1960s, but the product ranges that we recognise today, the 3-series, 5-series, 6-series and 7-series, were all introduced in the 1970s. The BMW M division, its in-house performance division, was founded in 1978, with the M5 being launched in 1984 and M3 in 1986.

In the 1990s, BMW bought the struggling British company, the Rover Group, which held the remnants of the large automotive conglomerate, British Leyland. The takeover was not successful and in 2000, BMW sold Land Rover to Ford, retaining MINI and its plant in Cowley, Oxfordshire, and sold the rest of the Group (including its Longbridge plant) to Phoenix Venture Holdings for nominally £10 as MG Rover. MG Rover subsequently went into administration in 2005, being bought by Nanjing Automobile group who became SAIC and relaunched vehicles in the UK under the MG brand. Ford subsequently sold Land Rover (along with Jaguar) to Tata Motors in 2008. The company, MG Rover Group, was formally dissolved in May 20235.

In 1998, BMW became the owner of Rolls Royce Motor Cars. The history behind the acquisition is complicated. When Rolls Royce Ltd was nationalised in 1973, Rolls Royce Motors was spun out and ultimately bought by Vickers Group, enabling Rolls Royce Ltd to focus on aero engine manufacturing. Rolls Royce Motors owned the ‘Spirit of Ecstasy’ mascot and grille design, but the aero-engine maker Rolls Royce plc (as it became known) retained the brand name and logo. In 1998, Vickers Group sold Rolls Royce Motors, which included both Rolls Royce and Bentley products, and both Volkswagen Group and BMW made bids for the company (BMW was already supplying engines). Rolls Royce plc licensed the brand name and logo to BMW, while Vickers sold Rolls Royce Motors to Volkswagen Group. BMW and Volkswagen reached a solution which saw BMW continue to supply engines to Volkswagen until 2002, after which the company that was previously Rolls Royce Motor Cars became Bentley Motors Ltd, and Rolls-Royce Motor Cars (established in 1998) became ‘the’ Rolls Royce car company, wholly owned by BMW.

Which brings us to today, with BMW being in full control of the BMW brand for both cars and motorcycles, the MINI brand and its assets, and Rolls Royce Motor Cars.

Business Performance

Products and Segments

The majority of BMW’s sales volume comes from the BMW-branded vehicles, with a little over 80% of sales volumes coming from this segment. A further 10% of volume comes from MINI vehicles, the majority of the rest from BMW Motorcycles, with Rolls Royce cars only accounting for a fraction of 1% of total corporate volumes. Volumes have been relatively stable, although 2024 has definitely been weaker than 2023, with 2024 Quarter 3 (24Q3) deliveries down around 12% since the same time last year (23Q3). Although total deliveries in the 1st half year in 2024 (24H1) was flat against the same period in 2023 (23H1), 2023 had a strong second half (23H2), whereas the second half of 2024 is showing a distinct slowdown.

By region, China is BMW’s highest-volume market, and the volumes have been dropping since the end of 2023. The USA, another significant market, has also been softening over the same period (Figure 2). China is approximately 30% of BMW’s deliveries, the USA around 15%, Europe (excluding the UK) around 33% - 34%, with Germany alone accounting for 12% - 13% of total deliveries, and the UK accounting for 7% of total deliveries, down from 9% in 2019.

A breakdown of the BMW product lines shows that the 3-series remains BMW’s highest-volume product, but volumes of the 1-series / 2-series and 5-series / 6-series have dropped significantly since 2019. BMW’s ‘X’ products have maintained significant volumes, although they have fluctuated somewhat over the years.

Looking specifically at BMW’s electrified products, it is clear that full Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) have been increasing in volume (and in terms of overall product share), while Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles have been similarly declining. Volumes in the electrified range are increasing while overall volumes have declined, and electrified products now account for almost 25% of BMW’s total deliveries.

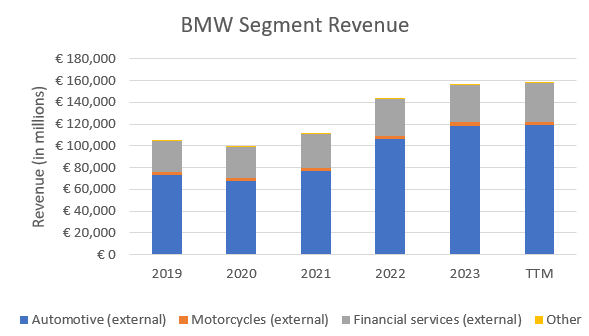

Looking at BMW’s segment revenue, around three quarters of BMW’s revenue now comes from its automotive division, with a little over 20% coming from its Financial Services, down from over a quarter in 2019. Motorcycle and Other revenues account for the final few percent (in Figure 5, I have shown only BMW’s ‘external’ revenue and excluded eliminations, meaning the sum of segment revenues is higher than their statutory reported number).

Operating Performance

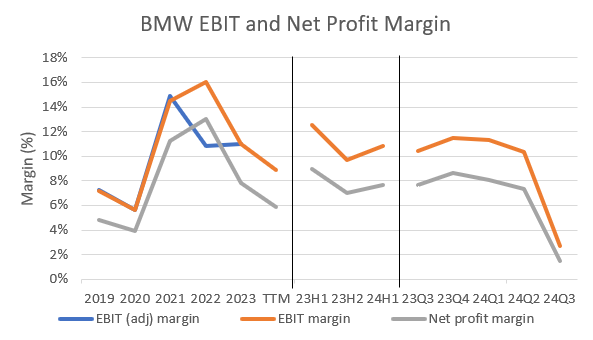

Looking at the margins of BMW Group, it is clear that they have fluctuated in recent times. Figure 6 breaks down gross profit and operating margins by year, by recent half-year, and by quarter. I have adjusted gross margin, where indicated, by excluding depreciation costs and R&D costs from Cost of Goods Sold (COGS). In 2019, these costs accounted for around 9 percentage-points of gross margin, however, now they are only 5 percentage points or so. Figure 6 also shows that margins have been fairly flat over the last year, until 24Q3, when they dipped heavily.

Operating margin, where indicated and where data is available, has been adjusted to exclude exceptional items. The fact that there is very little difference between the ‘adjusted’ and ‘nominal’ operating margins shows that there are not many exceptional items in BMW’s accounts. Operating margins have followed gross margin trends. Whereas operating margins had increased from around 5% in 2020 up to 12% in 2021, and remained at around 10% or higher since, with the recent drop in margin in 24Q3, operating margin is now back at the approxaimtely 5% numbers last seen during Covid.

Looking at earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) margin (i.e. operating income plus income from equity and other financial income), it is clear that margins have been dropping since 2022, and have dropped precipitously in 24Q3, to less than 2% net profit margin. 2022 saw a boost to statutory results through the consolidation of BMW Brilliance (BMW’s joint venture in China to produce and distribute BMW branded vehicles in China). Excluding this exceptional item, 2022’s EBIT margin was similar to 2023’s margin.

The culmination of the above is that earnings per share (after accounting for non-controlling interests) has dropped heavily from the €27 per share seen in 2022, and has become slightly negative in the most recent quarter, although EPS is still higher on a trailing twelve month basis than seen in 2019 and 2020.

Returns on Capital

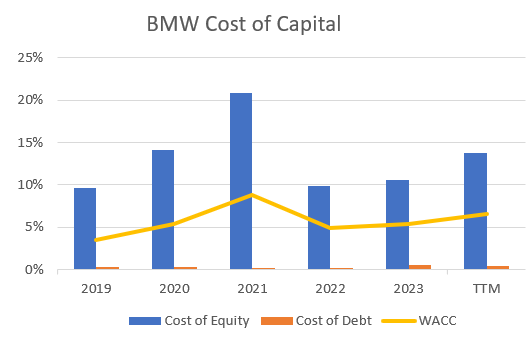

BMW’s interest cover is very strong, at over 10 through the period I am covering in this article (and has been around 20 in recent years). BMW’s nominal interest rate is very close to zero, but this is driven by the very large amount of financial receivables from BMW’s Financial Services division. Stripping this out, the cost of debt for BMW’s industrial operations has fluctuated between roughly 10% and 15%. This is much higher than the rate at which BMW is able to offer bonds (typically 3% - 5%), because the liabilities are shared between industrial operations and financial operations - the industrial operations is accountable for more of the interest payments but less of the total debt liabilities. Although BMW’s overall debt/equity is over 100% (down from nearly 200% in 2019), the debt/equity of its industrial operations is around 13%, which is now the highest it has been since before 2019, but is still relatively low in absolute terms.

Based on the overall cost of debt, BMW’s weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is around 6% - 7%. Cost of capital has been increasing since 2022 to almost 14%, close to the value seen in 2020. 2021 saw a very high cost of equity because the S&P 500 posted very strong performance that year, raising the bar for all equity investments.

Looking at returns on capital, the first point to highlight is that all of BMW’s return on capital metrics are above BMW’s cost of capital, meaning BMW can, on paper, generate positive returns on all of the capital it receives through either equity or debt. The second point is that BMW’s return on assets (ROA) and return on capital employed (ROCE) are now lower than they were in 2021 and have been dropping since 2022. Return on invested capital (ROIC) has fluctuated significantly, but has seen a heavy drop since 2023, it is now close to 2020 levels. However, in absolute terms, a return on invested capital of over 15% is still a reasonable number.

Cash Conversion Cycle

BMW’s inventory has increased 25% since 2023, which was itself elevated from 2022. With the loss of revenue seen so far towards the end of 2024, inventory has climbed markedly, towards almost 90 days’ of supply currently, which may lead to write-downs or increased sales incentives or reduced production to reduce inventory in the future, all of which could impact operating margins in the short- to medium-term.

This is occurring at a time when BMW are investing a lot in new capital expenditure (CapEx), outstripping their depreciation expenses and now accounting for almost half of their earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA). As a percentage of sales, CapEx has also been increasing, now standing at over 7%.

Looking at what these mean for cash generation in general, it is clear that cash flow from operations (CFFO) has typically been slightly higher than net income (CFFO/net income > 100%), while free cash flow (FCF) has been lower than net income. However, with the poor performance in the latter half of 2024, CFFO is currently significantly below net income, while free cash flow is now negative for the first time (on an annualised basis) since 2019.

(N.B. the spike in 2020 was caused by a significant change in receivables from cash financing, when BMW increased their provision for credit losses in relation to the coronavirus pandemic, leading to a reduction in net income without an associated reduction in operating cash flow.)

Valuation

To summarise the foregoing:

BMW have reasonable returns on capital, particularly returns on invested capital, although their returns have been dropping in recent years

The latter half of 2024 has seen some abrupt reductions in profit and in margins, and there is no indication that 2025 will be better than 2024. BMW have consequently rapidly built up additional inventory.

BMW are investing quite heavily in capital assets at the moment, leading to negative free cash flow

Performance, in general, has returned to the types of numbers last seen around the time of the Covid pandemic, although earnings are still (currently) better than seen in 2019 or 2020.

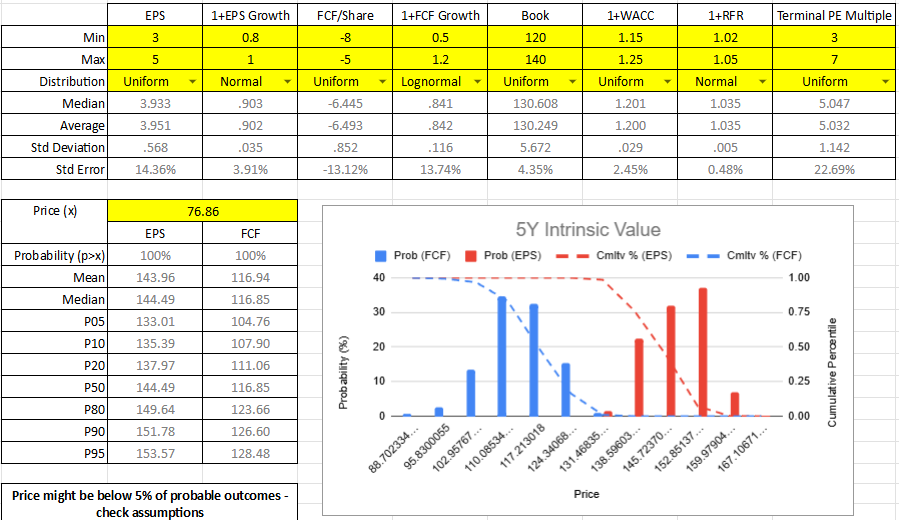

Putting some numbers into my Monte Carlo valuation, it looks like BMW could represent a value play at the moment, however, most of its value appears to be inherent within its book value, rather than its future cash flows (at the moment). Even if I assume free cash flow remains negative and future earnings sit around the range previously seen in 2019 and 2020, and although free cash flow may improve over time, earnings may reduce over time, then a fair value for BMW may well sit in the €110 to €130 range. This means BMW may erode a bit of its current book value, but would likely remain close to current levels of equity. If this is indeed a fair reflection of BMW’s intrinsic value, it would indicate a possible 50% upside to the current share price of around €77.

With the above assumptions, including the discount rate, it can be seen how much the future cash flows affect the intrinsic value of this stock - with my above assumptions, the future cash flows are small relative to the book value.

So would I buy this stock today? Despite the apparent value, I think there is too much risk of future short-term pain for the automotive sector, especially given the precipitous decline in earnings seen in just one quarter. I wouldn’t like to rely too much on the book value to realise the intrinsic value, which is a bit like relying on the stock needing to be liquidated to realise a return on investment, which isn’t going to happen (or would likely only happen once the equity value had been severely eroded and there was unlikely to be much liquidation value in the first place).

I am also not very impressed with the low operating margins, and I would want to see a sustained increase in these numbers before investing - I think BMW may find it difficult to accept further reductions in revenue without starting to sustain losses with such thin margins.

However, BMW does have a strong balance sheet. It is a firmly established brand and, if it can turn around the decline in its major markets, it could well prove to be a good investment at these prices, as it is currently trading at only a little over half of its book value.

The above article has been compiled with my own analyses and is intended for informational purposes only. It does not constitute financial advice or should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell any equities.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fokker_D.VII

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rapp_Motorenwerke

https://www.cycleworld.com/who-was-max-friz-kevin-cameron-top-dead-center/

Douglas, C. E. (2020). The Secret Horsepower Race. First Edition. Horncastle, UK: Tempest Books (imprint of Morton Books)

https://find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk/company/01595268